EDITION 43 - JANUARY 30, 2026

Your window into the stories, history, and ongoing work to preserve Yosemite’s climbing legacy.

A Note from the Editor

Warm, clear conditions remain in Yosemite and the surrounding foothills. It’s been 18 days since it rained, and the forecast shows nothing but blue skies and scattered clouds. With lows in the 30s at night and highs in the 50s to upper 50s, climbing conditions couldn’t be better.

As for Tuolumne Meadows winter conditions, Laura and Rob Pilewski posted on NPS.gov:

It was a quiet weather week across the Tuolumne Meadows area. The average high temperature was a balmy 56 degrees, which is 16 degrees above the January average. Other than some NE ridgetop winds, it was mostly calm.

If it were March, we would be talking about the melt/freeze cycle and the impending corn harvest. But alas, the calendar reminds us that it is still January. Although we were able to find some spring-like snow on open solar aspects at the middle elevations, the shady places still hold cold and dry winter snow. Despite daytime temperatures being well above freezing, the snow remains cold and dry due to short days and low humidity. Although there are variable snow surface conditions out there, coverage and ski conditions are excellent.

Snow line still extends to the gate in Lee Vining Canyon.

I climbed at Arch Rock with Pat Curry and company last Saturday. It was cool enough that I didn’t have to chalk up every few moves, and I could get in the flow as we ran laps on standard lines: New Dimensions (first pitch), Midterm, and Axis (aka Blotto). Our crew grew by a few members on that lovely winter day at the crag, with Pat bringing in Jake from Tracy, and me recruiting Josh from Midpines.

And although the climbing and crew were phenomenal, I couldn’t wait to get home and watch Alex Honnold climb Taipei 101 on Netflix.

Netflix is now streaming Free Solo (and Meru). For Red Bull, I’ve penned a few stories on Honnold and company. Read more here:

Climber Alex Honnold on the life lessons that followed Free Solo

Since the release of the Oscar-winning film, climber Alex Honnold has made first ascents in Antarctica, set the Nose speed record with Tommy Caldwell, and helped his foundation grow

The incredible career story of acclaimed climber and filmmaker Jimmy Chin

The director of Meru and Free Solo and Oscar award-winning moviemaker says his film work is only his part-time job. He still thinks of himself as a simple skier and climber at heart.

In the news this week, Owen Clark at Outside writes:

Vandals Just Defaced Yosemite. They Scrawled This Tag on Rocks and Signs.

“Yeti” was tagged on boulders and several signs in the park

For this week’s Founder’s Note, Ken Yager writes about his first serious attempt to climb the Nose in winter, where he learned hard lessons in logistics, cold bivies, and a sketchy retreat.

And for this week’s feature story, I talk with Heide Lindgren and her fiancé, Marc Manko, about their love of climbing in Yosemite. A few years ago, Lindgren and I ran the trails at Stockton Creek Reservoir in Mariposa, and later she joined my friends and me bouldering above town. She took to it immediately, and over the years, she’s kept me updated on her progress—today, living in Boise, Idaho, she’s a 5.10 lead climber.

In 2022, we rode e-bikes to Mike Corbett’s memorial at the Yosemite Climbing Museum in Mariposa, and later that day, we rode over to the Yosemite Boulder Farm across town. That’s where I met Jerry Gallwas.

Heide and Marc frequently visit Yosemite, where she has done both single- and multi-pitch climbs in the Valley. This summer, she is aiming for Snake Dike on Half Dome. Like me, she’s a dog lover, and she even has an Instagram page for her chihuahua. Check it out at Mae West Unleashed. This week’s feature is on Heide, and next week’s will focus on Marc.

Chris Van Leuven

Editor, YCA News Brief

UPCOMING EVENT

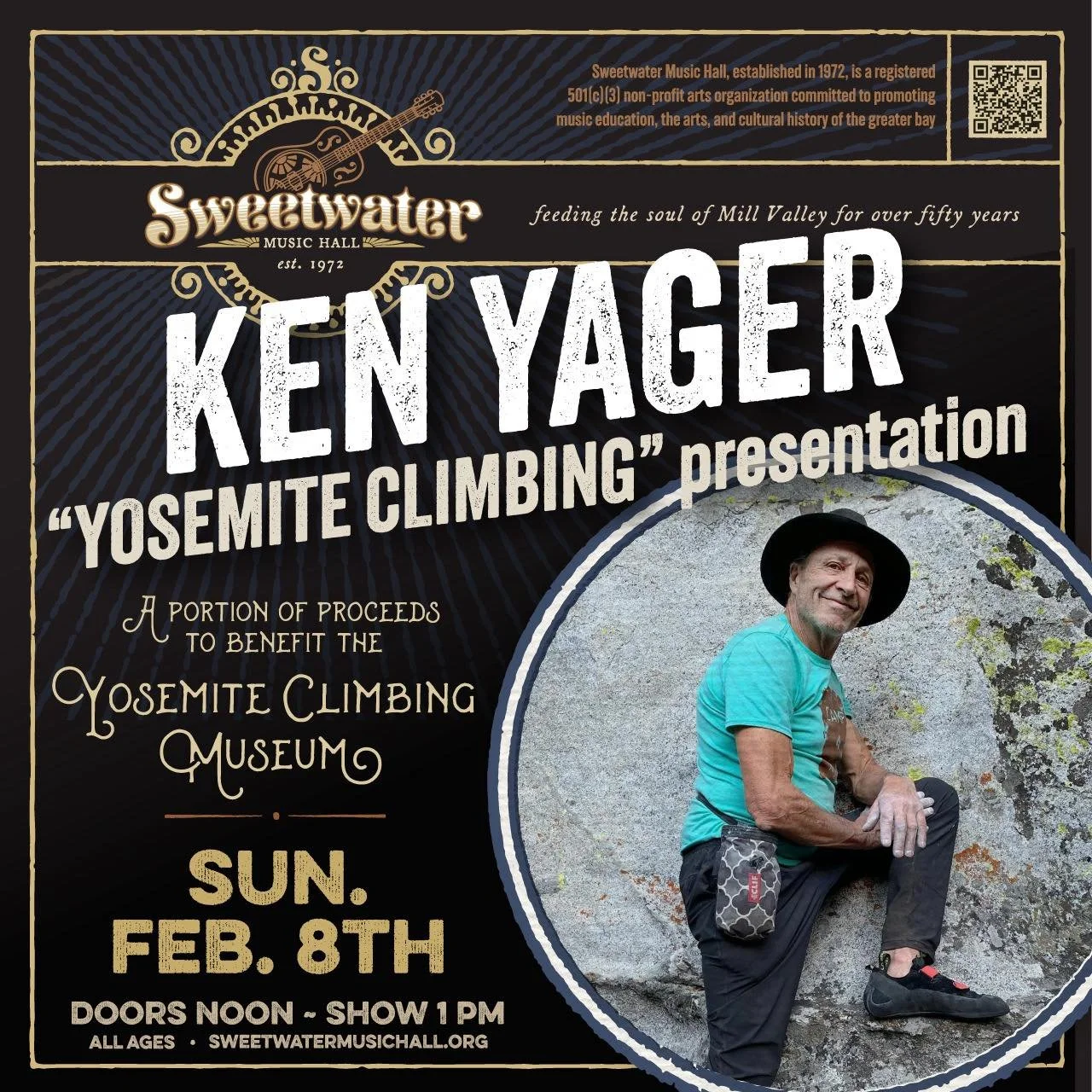

Join Ken Yager on Sunday, February 8th at Sweetwater Music Hall in Mill Valley, CA for an exciting Yosemite Climbing Presentation!

Ken Yager brings “Yosemite Climbing” to the stage for an inspiring presentation celebrating Yosemite’s climbing history, community, and conservation. All ages are welcome and a portion of proceeds benefits the Yosemite Climbing Museum.

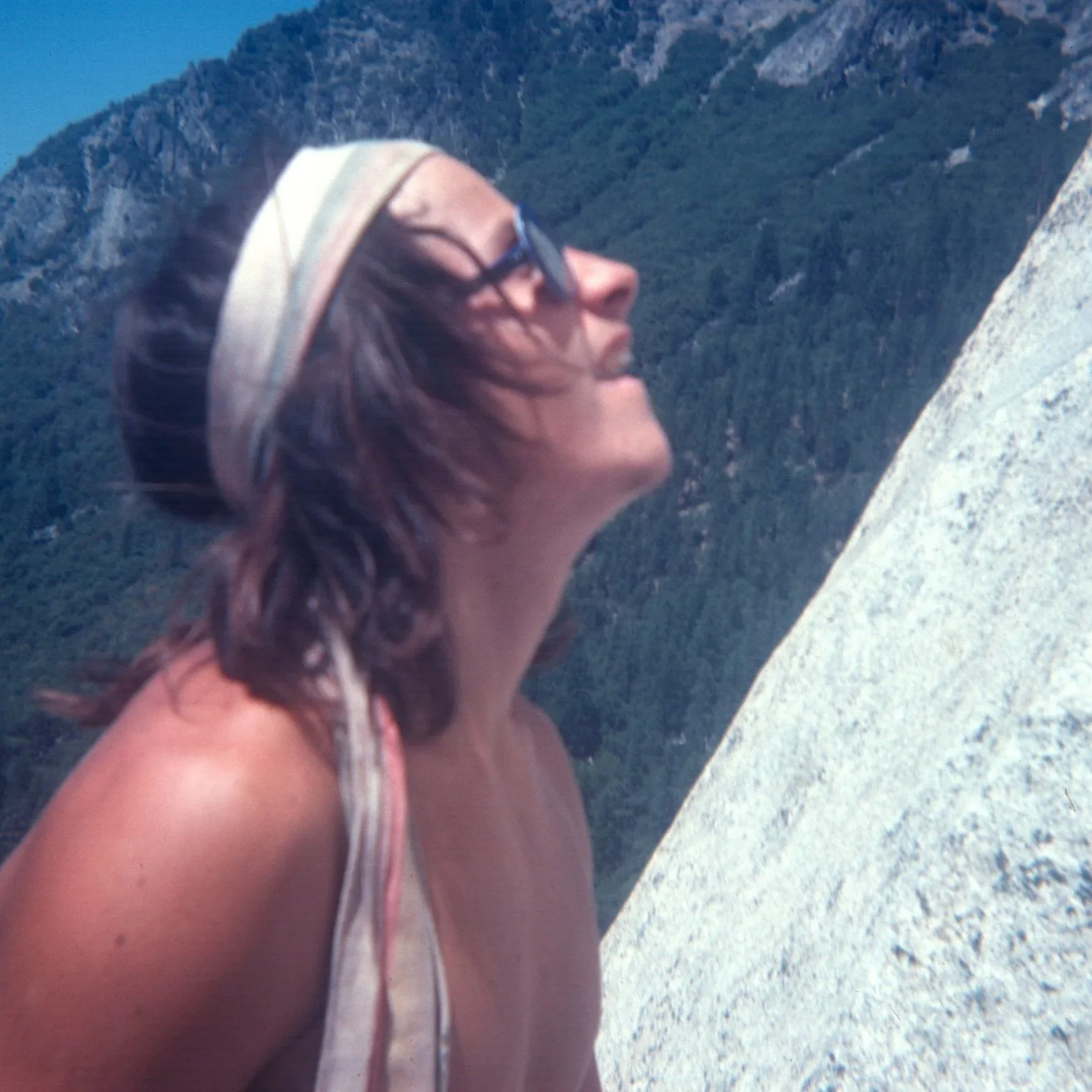

Heide on her first trad lead, Intruding Dike at the City of Rocks, Idaho. Photo: Marc Manko

Heide Lindgren: Finding Her Feet on Yosemite Stone

From her first hesitant moves on Mariposa boulders to leading 5.10 and setting her sights on Snake Dike, Lindgren’s climbing story is rooted in community, confidence, and learning how to breathe when things get hard.

Six years ago, I met Heide Lindgren in Mariposa through her then-husband, back when she briefly lived in town. Originally from Boca Raton, Florida, and fresh off a long stretch in New York City, she didn’t have much of a mountain background. But one afternoon, she joined my crew at the local boulders, watched us move over stone, noticed how snacks got passed around as easily as beta, and something clicked.

She liked the challenge. She liked the support. And she liked the people.

“I never thought that I would be a climber, or that I would move to a town on the outskirts of the most famous climbing area in the world,” she later wrote in The Culture-ist. “I was content living the life of a student and model in New York City.” She went on: “I knew that I would find a new world out there vastly different from the one I called home for so many years, but I had no idea how transformative climbing—and living in the risk-taking capital of the world—would be, or the impact the people would have on me.”

Her first Yosemite climbing experience was bouldering with me, but it didn’t take long for her to realize she preferred roped climbing. When she began dating longtime climber Marc Manko—now her fiancé, with a June wedding coming up—she started building a lead head and logging real mileage. And she’s shared her progress with me. Together they cragged and climbed multi-pitch routes in Yosemite Valley, taking climbs move by move and pitch by pitch.

Her first multi-pitch was The Grack on Glacier Point Apron, which was also her first time rappelling. She froze at first. With Marc’s steady encouragement, she worked through it. And then, it clicked. Next, they climbed After 6 at Manure Pile Buttress.

Over the years, Heide kept coming back through the Sierra foothills, visiting Mariposa while Marc ticked off big objectives—including the Nose (twice) and the Steck-Salathé on Sentinel, and she quietly worked her way up the grades. Today they live in Boise, Idaho. Heide will be studying mental health counseling this fall in grad school, runs a fitness and wellness coaching business, and still models. Marc works as a physician assistant in emergency medicine. They climb several days a week at their local gym, The Commons, and make regular trips to City of Rocks, the Sawtooths, and Hells Canyon.

I still remember her first text telling me she’d led her first route. Then another. Today, she leads 5.10, though she’s the first to admit it’s rarely smooth.

“It just involves a lot of me yelling, ‘I can’t do it,’ and a lot of him going, ‘You got this,’” she says. “Then I realize I can’t be yelling anymore because I’m trying to breathe. So it’s like, ‘Shut up and climb.’”

Now, she says, it’s about confidence.

“Climbing has been a gift in my life,” she recently wrote on Instagram. “It’s an opportunity to grow as a person. Sometimes the mental toughness it demands is even more than the physical.”

Over Christmas, she texted me from Hells Canyon. It was colder than Yosemite—high of 44, sunny—but spirits were high. She’d picked up a miniature expedition tent from REI, the kind usually meant for display, and tucked her chihuahua, Mae West, inside to stay warm while they climbed. The dog stayed put, gave her some serious side-eye, and they climbed.

This summer, after their wedding, Heide plans to return to Yosemite with Marc with one clear objective: Snake Dike on Half Dome.

“Yes,” she says simply. “That is what I want to do.”

Heide following the first pitch of After 6, Yosemite. Photo: Marc Manko

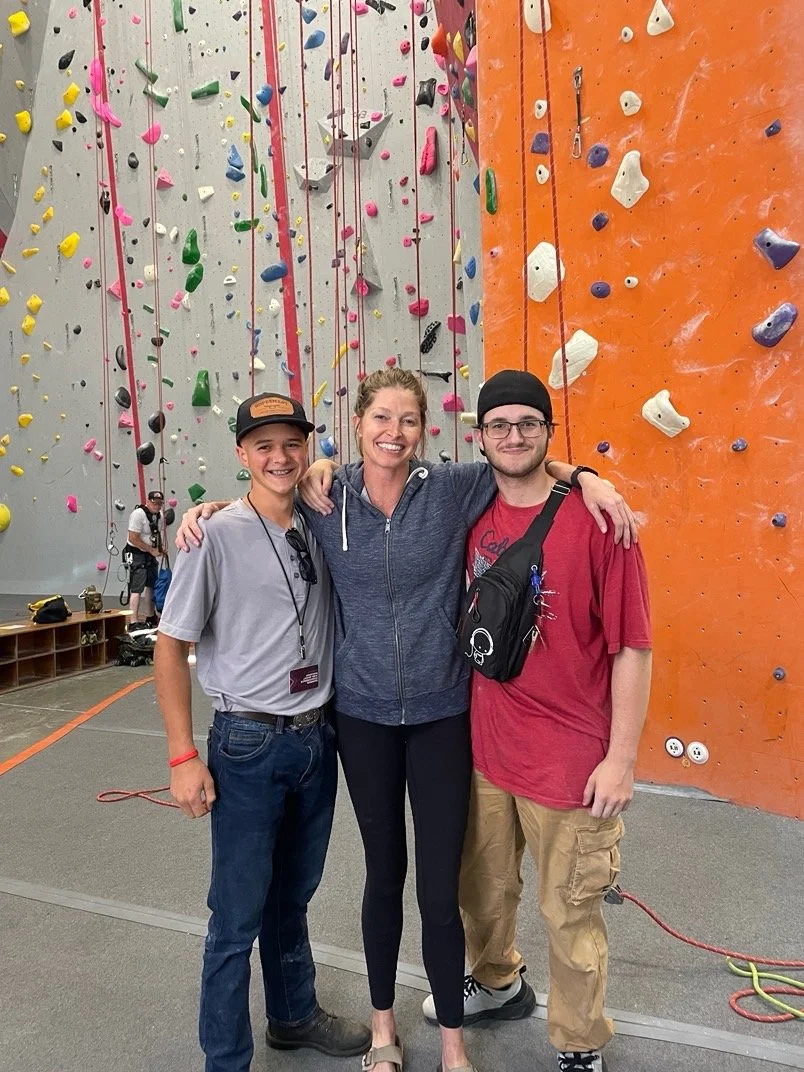

Heide with two kids from Courageous Kids Climbing. Photo: Lindgren collection.

Heide at the City of Rocks. Photo: Marc Manko

The Nose Attempt

Founder’s Log | By Ken Yager

I had just moved to Sunnyside Campground (Camp 4) with the intention of climbing El Capitan. After a week, I determined the only other person interested in doing the same was Mike Corbett. Mike had done a Grade V ascent of the Rostrum, so he had experience. I had tried four walls and didn’t make it up any of them. We decided to go for the Nose. We pooled our gear together and borrowed what we didn’t have. We bought our food at the Village Store. I was 17, and Mike was 23. It was mid-December of 1976. Being a drought year, it was cold at night and perfect for climbing during the day.

Early in the morning, we got a ride from a friend to the trailhead at the base. It is a short hike, but it feels a lot longer with a heavy load. The climber’s trail weaved through thick trees growing in a talus field. It was dark in the trees even though it was getting light out. We warmed up quickly as we stumbled up the trail. Popping out of the trees, the view of El Capitan was unobstructed. We were close to the start of the Nose and stopped to look at it before continuing. I felt a shiver of excitement.

At the base, we dropped our packs and studied our topo map, re-memorizing pitches we already had memorized. We emptied the pack and haul bag, then repacked the bivy gear, clothing, and water so it all fit into one haul bag. Mike and I each uncoiled a rope—one to lead with and one to haul the bag. I put my swami belt around my waist, stepped into my newly purchased Forrest leg loops, and attached them with a carabiner. My swami belt was made of 2” webbing wrapped three times around my waist and tied with a water knot. Before that, I had a 1” webbing swami, and I was glad I upgraded to 2” webbing for the extra padding.

We started climbing and belaying with hip belays. Our rack was stoppers, hexes, and pitons. The first part was broken up, making it easy to climb but hard to haul. Working together, we got the bag to the start of the real climbing. We climbed well together and were pleased to reach Sickle Ledge as darkness hit. Our friends from camp were yelling and cheering us on. We were exhausted but in good spirits as we chose spots among the rocks and made beds with thin Ensolite pads, extra rope, and whatever padding we could find. We dug through the food bag with faltering headlamps. We mainly had canned food—Van Kamp’s Beanee Weenee and mandarin oranges for dessert. Enjoying the moment under the stars, we stayed up later than we should have.

The next morning, before the sun rose, a cold breeze blew in and chilled us. We stayed hunkered down in our sleeping bags until the sun warmed us. There was not going to be an alpine start. I was stiff and sore as we started climbing, but we moved well once we got going. We could hear people yelling our names, which made us not feel so alone. The late start was a mistake. We ran out of daylight in the Stoveleg Cracks about 150 feet below Dolt Tower—our intended ledge for the night. Our headlamps died, and we were blanketed in darkness. We weren’t going anywhere and realized we were spending the night here.

We didn’t have hammocks. They would have been useful. We did each have a nylon belay seat—commonly called a butt bag. Carefully avoiding dropping anything, we slipped into our sleeping bags and sat back into our butt bags. We repeated dinner, drank a little water, and slumped against the wall, dozing. It was an uncomfortable night disrupted by cutoff circulation and cramping. We welcomed the first light. When the sun hit, cold winds swirled around the face, and we started shivering violently. We weren’t moving fast enough and would run out of food and water. The days were short. The decision was made to retreat.

A couple of friends walked up to the base. We let them know we were coming down; they sat in the sun to watch. We packed what we wouldn’t need for rappels into the haul bag. Yelling “Rock” several times, we threw it off. It exploded on impact, flinging items out of the top. Oops. Our friends gathered it up.

We used six oval carabiners to create a friction device called a brake bar for rappelling. This was the standard at the time. I led the rappels with Mike following. My rope was at least 10 feet shorter than Mike’s. They were both supposed to be 150 feet. The knot tying the ropes together had to be five or six feet below the anchors to even them out, which became awkward on hanging anchors. We had to set up below the knot, then hand-over-hand down until we could start the rappel. We tied the ends together to keep from rappelling off the end. It went well until the crackless face below the Stovelegs, where the anchors were hanging on a blank face. Some were rope-stretchers, using every inch to clip into the bolts. The bolts were threaded with wads of slings, so you clipped into the slings. On one rappel, I took my prusik off and let go of the ropes as they sprang up, out of reach. Oops. After that, I kept the prusik on until Mike reached the anchor and we were ready to pull the ropes. I had never done such long rappels before. It was terrifying.

One rappel was particularly memorable. I ran out of rope with my brake hand at the knotted end. The anchor below was out of reach. I saw a single rusted buttonhead bolt two feet below and off to the right. Weighting the prusik, I swung over and barely clipped into it. Nearly half the head was missing. I girth hitched my remaining slings together—including my hammer sling—attached them to my prusik on the rappel ropes, and clipped in. Then I untied the knot, gaining nearly two extra feet of rope, and rappelled off the end onto the manky bolt. I expected it to break. It didn’t.

With only crack gear and my aiders left, I clipped both aiders to the bolt and could see they reached the anchor below. I backed them up to the prusik and slings and climbed down, belaying myself. I clipped into the anchor and clipped the end of my aiders there, too, to back Mike up.

Mike came down, not pleased. He had no choice but to clip the same bolt, then pull ropes and rappel from it. His only backup, if the bolt sheared, was my aid slings. He rappelled off the ends, gently bouncing onto the bolt, then pulled the rope with a prusik until he could tie in. I gave him a hip belay as the rope whipped down. He made it to the anchor and clipped in. We were relieved. We had been lucky. That could have ended very differently.

We rappelled to the ground without further incident and met up with our friends. Mike and I had bonded as only a climbing adventure can do. We continued to climb together throughout the winter. We got Forrest hammocks and customized them with footbags and clipping loops. We acquired a bolt kit. We each had a 165-foot rope. The days got longer, and we ventured onto longer routes: two routes on Washington Column, the South Face and the Prow, and the West Face of the Leaning Tower. Six months after our first attempt, we tried El Cap again and climbed it for the first time.

PHOTO OF

THE WEEK

Matt Cornell on Astroman. Photo: Chris Van Leuven

Stay up to date on the latest climbing closures in effect!

Get your permits, do your research, and hit the wall!

Visit the Yosemite Climbing Museum!

The Yosemite Climbing Museum chronicles the evolution of modern day rock climbing from 1869 to the present.

The YCA News Brief is made possible by a generous grant, provided by Sundari Krishnamurthy and her husband, Jerry Gallwas