EDITION 42 - JANUARY 22, 2026

Your window into the stories, history, and ongoing work to preserve Yosemite’s climbing legacy.

A Note from the Editor

Warm temps are continuing in Yosemite and here in the Sierra foothills, where I’m writing from. It’s cloudy today and expected to stay cloudy tomorrow. In Yosemite Valley, it’s in the low 50s right now, with highs forecast to hover in the upper 40s to upper 50s over the next week.

Last weekend, I climbed at the Finger Lickin’ crag in the park with Nick Miranda and our mutual friend Daniel Melenedrez. It was sunny and even warmer than it is now, and I showed up in shorts and a T-shirt and felt perfectly comfortable. We started with the first routes you come up to, did a few 5.10 splitter cracks—ranging from fingertip to wide hands and offwidth—and got in some laps before calling it early. We spent the rest of the afternoon relaxing by the Merced River, soaking in the scenery.

In climbing news, Tom Herbert messaged me this week that he put up a new line. He wrote:

“Good evening. I put up a cool, new route on Loggerhead Buttress called Winter Sport. It is on Mtn. Project. There is a fixed line on it. If you are slab-fit, go do it!”

Winter Sport is a 35-meter, single-pitch arête on Loggerhead Buttress that faces south, so it receives sunlight most of the day, making it a good choice when you want something warm and quick.

Nearby is the first pitch of Cornershop (5.9). Connor Herson made the second ascent of Winter Sport.

When I look up Yosemite, my Apple News feed is filled with stories on the upcoming Firefall.

LA Times staff writer Christopher Reynolds wrote: With Yosemite ditching reservations for firefall, will it be a mess? Here's what to know.

Yosemite's firefall — the winter convergence of sunbeams and falling water that has drawn growing crowds to the national park's Horsetail Falls — will be different this year. At least for those hoping to plan a trip.

When skies are clear and Horsetail Falls is flowing, the firefall phenomenon happens in mid- to late February as the setting sun illuminates the falls for a few minutes before disappearing, giving the water a lava-like orange glow. A hazy or cloudy evening can dramatically reduce or destroy the effect. Yet since photographer Galen Rowell captured a striking image in 1973, thousands of visitors (many of them photographers) have made the journey, vying for the ideal position, prompting various safety measures.

And Stephanie Vermillion at Travel + Leisure wrote: This National Park Has a Waterfall That Turns Fiery Orange Every Year—How to See It

Mid to late February, when the sun is perfectly positioned to cast its tangerine glow, is the time to spy it… The phenomenon occurs about 20 to 25 minutes before sunset. You need at least patches of clear skies—just enough for the sun to shine through. But don’t give up if the weather looks rough; even a brief hole in the clouds can spark a fiery show.

Climbing Magazine reported:

When he topped out on 'Free Rider' (5.13a; 3,300ft) on November 30, Teddy Eyob (@goretex_jockstrap ) became the first Black climber to free El Capitan.

It was a milestone decades in the making—even if it wasn’t one he ever set out to chase.

In an exclusive interview with Eyob, we get the details of his ascent, how he tackled the crux Boulder Problem, and his insights on access in our sport.

In this week’s Founder’s Note, Ken Yager shares a classic Yosemite story that starts in the late ’80s, when plastic holds and indoor competitions first appeared in the U.S.—right in the middle of the bolting wars—and eventually leads to a garage in El Portal. A few boxes of early climbing holds turn into a full training cave, complete with duct-taped problems, darts, and malt liquor—where a strong local named Cade Lloyd becomes a regular. From there, the story shifts to El Cap and Cap’s Eagle’s Way, through blistered hands, brutal hauling, and a scare when Horsetail Falls comes alive above them.

For this week’s feature, I chat with Midpines local Nick Miranda. I’ve been climbing with Nick in Yosemite for several years now, often cragging in the Lower Canyon or sport climbing at the Chapel Wall. We’ve shared burns on Crimson Cringe, meandered our way up Super Slacker Highway, and sessioned Red Zinger more times than I can count. What I appreciate about climbing with Nick is that he’s always positive, gives his best, and keeps it mellow. We’re not chasing grades. We’re focusing on efficiency, refining our technique, sharing a few laughs, and, most importantly, staying safe. I’ve seen him climb enough to know he’s more than capable of reaching 5.11 and beyond, but that’s not his goal. “I look at it for what it is—it’s fun, and it’s part of my life now,” he says.

Chris Van Leuven

Editor, YCA News Brief

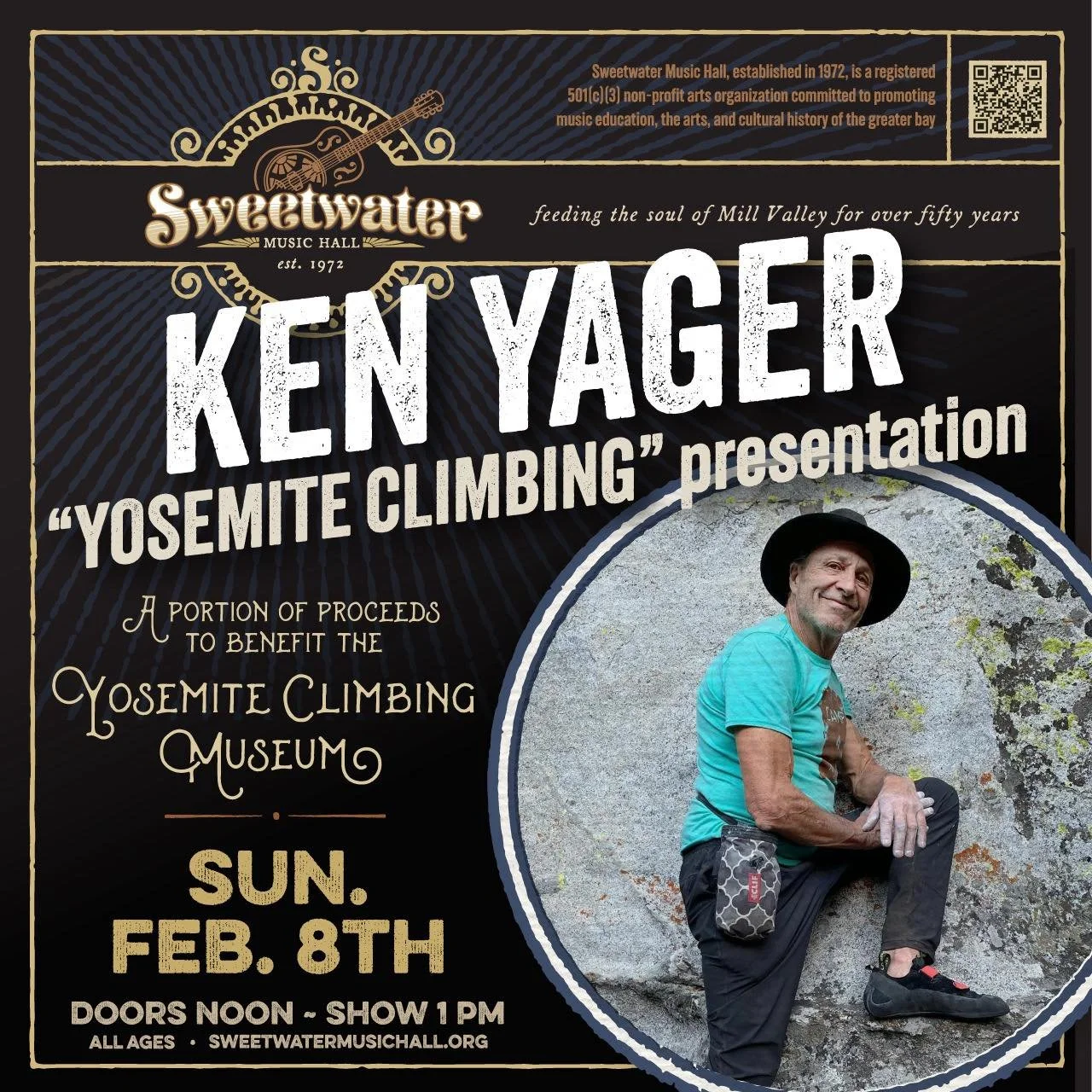

UPCOMING EVENT

Join Ken Yager on Sunday, February 8th at Sweetwater Music Hall in Mill Valley, CA for an exciting Yosemite Climbing Presentation!

Ken Yager brings “Yosemite Climbing” to the stage for an inspiring presentation celebrating Yosemite’s climbing history, community, and conservation. All ages are welcome and a portion of proceeds benefits the Yosemite Climbing Museum.

Nick Miranda on Super Slacker Highway in Yosemite. Photo: Chris Van Leuven

Nick Miranda and the Living History of Yosemite Climbing

From learning climbing movement in the Curry boulders to leading Astroman and stepping onto big walls, Miranda has built his Yosemite apprenticeship the old-fashioned way: pitch-by-pitch, with the Valley’s past—and present—always in view

“What do I love about climbing in Yosemite? A lot of things—especially the history,” Nick Miranda told me from his small wood cabin in Midpines during this morning’s call.

Nick wasn’t just talking about Harding and the Golden Age of the late ’50s and ’60s, the Stonemasters in the ’70s, the sport climbing revolution that followed, or today’s era of big-wall free climbing. He was talking about the growing history that Yosemite still is. He mentioned running into Keenan Takahashi, Katie Lamb, and their crew at the boulders recently. “You see those people at the boulders, and you’re just like, ‘dude, these are the legends.”

When Nick and his brothers moved to Yosemite in 2010 and he got work as a janitor for the concession, he’d never climbed before. Over three seasons with that gig, he fell into the scene fast. During this time, he and his siblings got on the rock for the first time. Together they learned how to build anchors, how to move over stone via the Curry bouldering circuit, and the basics of trad climbing. Nick liked the simplicity of bouldering—just you, a crash pad or two, and some buddies. By his second year, he was leading.

“When I started, my progression was really quick because I was super into it,” he says. “Once we got ropes, we top-roped everything we could. That’s what’s cool about climbing, you’re just thrown into the fire.”

He learned systems the way many self-taught climbers do: trial and error, and eventually someone pulling you aside to say, “Hey, you’re doing that wrong.” Early on, he and his crew realized they’d been belaying incorrectly with an ATC and had to relearn the fundamentals.

They didn’t have a complete trad rack between them, so they built one the only way they could—piece by piece, one person at a time. Someone would buy a cam, someone else would buy another, and they’d combine them into a usable rack. They shared a rope, shared gear, and kept getting out.

Within his third year, Nick and his brother Rich went for Astroman—1,000 feet of 5.10 and 5.11 and one of the most famous long trad routes in Yosemite, if not the world. Between the sustained jamming, the claustrophobic Harding Slot, and the notorious last pitch, it’s a full-value Yosemite trad experience. They got it done in a day, topped out before dark, and then walked off in their climbing shoes as they didn’t bring approach shoes.

They fell at the cruxes, pulled through where they could, and battled for every pitch. “We made it up by any means,” he says.

“On the Harding Slot, I kind of had a meltdown—my helmet got stuck. I didn’t like that pitch at all. When my head got stuck, I grabbed the rope above me and pulled through.”

While most of Astroman is physical hand-jamming, the last pitch is a different kind of problem. Protection thins out, and the leader has to commit to technical face climbing—sometimes on little more than smears for feet—above a long stretch of consequence. Nick took the sharp end anyway and finished the job. “I was proud to lead the last pitch out of there,” he says.

From there, his sights shifted to big-wall aid. He ticked off what he calls “little big walls,” with multiple laps on Leaning Tower and Washington Column. This past year, he climbed the Salathé Wall with his girlfriend, Lydia (see last week’s News Brief), and Max Crouch, and later climbed the Nose with young up-and-comer Dan Levitt.

These days, he says he’s not in peak shape. His work in rope access and tower climbing can keep him away from Yosemite for months at a time, and it shows when he comes back. He wants to return to the basics—movement, efficiency, and confidence—especially after backing off from Flying in the Mountains at Parkline Slab last week, where he felt unsteady and pumped, despite cruising similar terrain in the past. He’s most psyched on bouldering at the moment.

Thinking back to his early Yosemite days, he remembers the mental edge that came with learning on the sharp end. “When I was doing hard stuff back then, I was just trying to make it through. There was this gray cloud—like, ‘Am I going to make it or not?’”

“Now, I try to go more prepared if I’m gonna take something on.”

Nick Miranda on Super Slacker Highway in Yosemite. Photo: Chris Van Leuven

Cade Llyod

Founder’s Log | By Ken Yager

Cade Lloyd on Eagles Way. Photo: Ken Yager Collection

In 1988, competitive climbing on artificial holds was introduced to the United States at Snowbird, Utah, where a 115-foot plywood structure at the Cliff Lodge was equipped with fiberglass resin holds. It marked the start of indoor climbing in the U.S., and most climbers weren’t particularly enthusiastic about the plastic—except for a few who saw it as a valuable training tool.

It landed in the middle of the bolting wars, when sport climbing and rappel bolting were reshaping the landscape, while old-school ground-up climbers pushed back. The two worlds didn’t always mix well.

A year later, Peter Mayfield opened Cityrock in Emeryville, California. Around the same time, I lived on the edge of Yosemite National Park in El Portal and spent my free time climbing both in the park and on the East Side.

Peter gave me a couple of boxes of holds he didn’t need anymore—many from the first Snowbird competition, including textured 6-sided panels made by Entreprise. I built a traverse in my garage and did laps until I couldn’t hang on any longer. I added an overhang, and when holds got too expensive, I started making my own from seasoned black walnut. The garage turned into a training cave.

I started getting strong, my free climbing improved, and word got out. I marked climbs with duct tape, and people began showing up—first on rainy days or at night, then nearly every day.

That’s where Cade Lloyd entered the picture. A group of three climbers from Best Bet often came down to train in the evenings, and Cade was there more than anyone. He was solidly built and strong, wore his brown hair long with a mullet that gave him a Wolfgang Güllich look, and had a mischievous grin with a slight underbite. He was funny, sharp, and not afraid to call someone out if they were contradictory.

We’d mark problems we hoped only we could do, run informal competitions until we peeled, then play darts to rest. Plenty of beer was involved, and the Best Bet crew’s drink of choice was Old English 800.

Cade often swore Eric Kohl was drinking his beers. One night, Cade walked in grinning and said, “Check this out!” He’d punched a hole under the top of his can with a dart so Eric wouldn’t know to cover it with his thumb, and it would dribble down his shirt. The only problem was that Cade kept forgetting, too. By the end of the night, both were soaked. Eric looked down and said, “I must be rummy. I'd better go to bed,” and stumbled off while Cade burst out laughing.

At that time, I was working on federal underground construction projects in Yosemite Valley as part of the Capitol Improvement Plan, so my climbing mostly took place on weekends. The garage kept me fit and connected me to the scene.

Cade was trying to get up on El Cap to climb Eagle’s Way, a Mark Chapman and Jim Orrey route on the far-right side of El Capitan, but his partners kept bailing. Then people started telling me they heard I was going up there with him. I laughed, “What?” “No, I’m not.” But the rumor spread until it felt like town truth—because Cade had started it.

When I called him out, he admitted it with a chuckle and dropped the clincher: “It might be awkward if you don’t. Everyone thinks you are going. Do you want to tell them you aren’t?” I said, “Cade! You son of a bitch!” He just chuckled. He knew he had me. And truthfully, I wanted to do a wall with him too, so I took two extra days off, and we went.

We hiked to the base on a hot morning with food and water. Cade had a pitch fixed and a haulbag waiting. The hauling was brutal right away, and I got blisters fast, but we moved efficiently once we were established.

On day two, I led the Seagull, the first A4 pitch. I didn’t notice the weather turning until I reached the anchor and felt rain. Under the overhang, it cooled off—brief relief—until it intensified and we realized we were directly under Horsetail Falls. We heard the climbers yelling on the Zodiac as water poured over the rim. The last thing I heard was “Oh my god! Look at those guys,” and then the Fall engulfed us, and it became completely silent.

The water wasn’t hitting us at first—it was falling out from the face—but it was brown with debris. We saw a dead tree spinning by in the water. Cade immediately started climbing diagonally out to the left to get us out of the fall line while I belayed and tried not to think about what would happen if the water shifted a few feet.

Cade got established, hauled, and I jugged out from under the worst of it. The storm tapered, sunlight broke through, and suddenly we were warm again, watching the rock steam as it dried.

That night, Cade pulled out two Old English beers and handed me one. A cloud of swifts swept past and circled back. Cade laughed and said, “They like you, Yager”. One bird slipped into the crack above my head, and then hundreds followed—because I’d built my anchor right at the entrance to their home. Cade couldn’t stop laughing.

We topped out as darkness hit on the fourth day. The next morning, I went straight to work—late—only to find the owner visiting from Arizona. Uh oh! I got reprimanded and punished with the gnarly jobs for the rest of the contract. Yosemite is a small town, and everyone seemed to know we’d been up there.

I couldn't care less. I’d climbed El Cap off the couch with my friend Cade; we’d been challenged, and we’d made a good team. Plans were made to do a new route on Elephant Rock once my job ended. Meanwhile, we kept training in the garage and playing darts.

PHOTO OF

THE WEEK

Tom Herbert on Midnight Lightning. Photo: Chris Van Leuven

Stay up to date on the latest climbing closures in effect!

Get your permits, do your research, and hit the wall!

Visit the Yosemite Climbing Museum!

The Yosemite Climbing Museum chronicles the evolution of modern day rock climbing from 1869 to the present.

The YCA News Brief is made possible by a generous grant, provided by Sundari Krishnamurthy and her husband, Jerry Gallwas