EDITION 40 - JANUARY 8, 2026

Your window into the stories, history, and ongoing work to preserve Yosemite’s climbing legacy.

A Note from the Editor

Well, the eluge of storms have finally cleared over Yosemite, leaving the park a beautiful winter wonderland.

Looking at the Yosemite High Sierra webcam (about 8,000 feet), Half Dome and the surrounding high country are coated in deep snow. Down on the Valley floor, the Half Dome cam shows a thin layer of snow and mist rising from Ahwahnee Meadow. Lows are in the 20s and highs are mainly in the 40s, but it’s warming over the weekend and highs are expected in the mid-50s by next week.

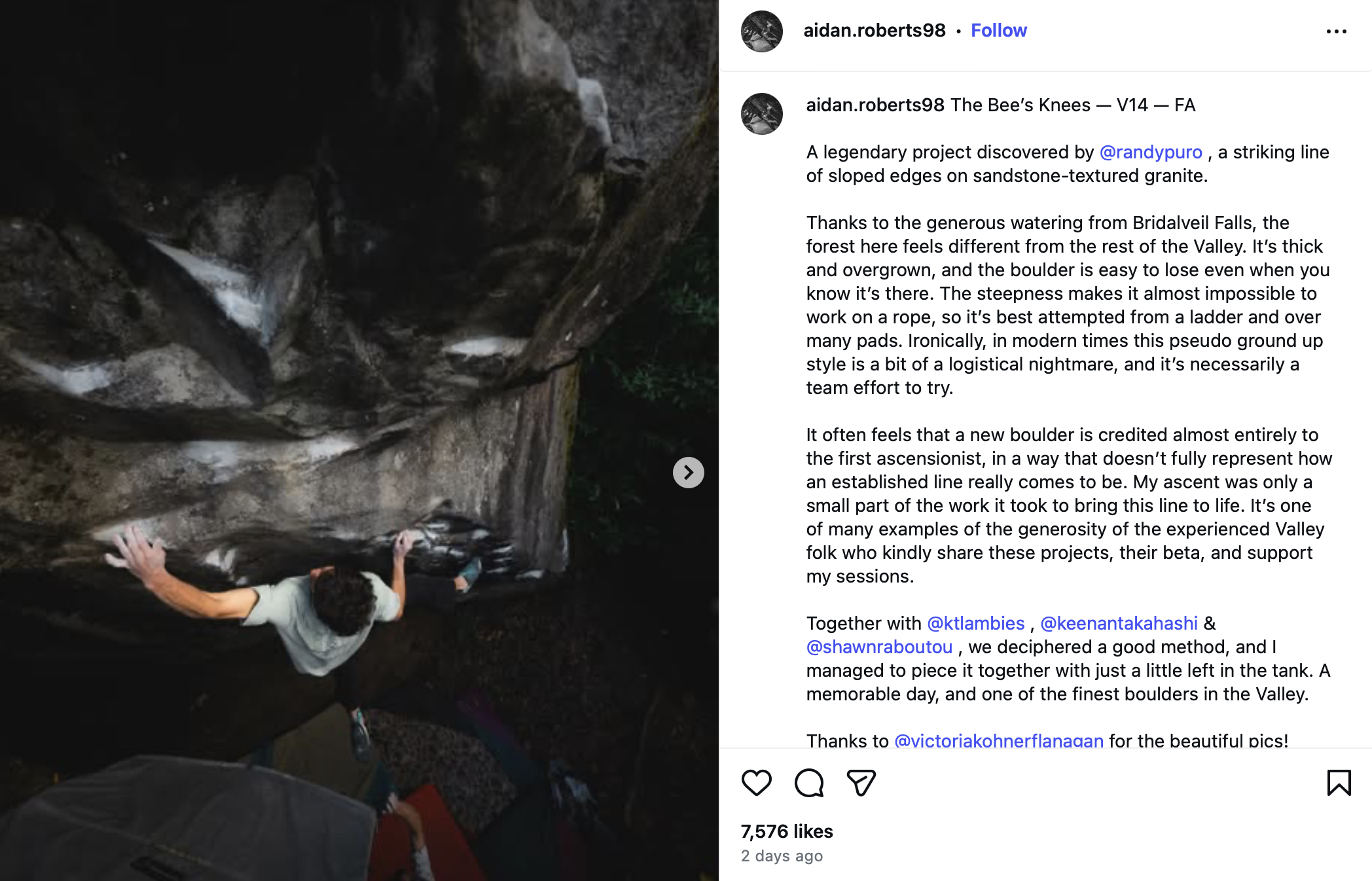

Yosemite bouldering made the news in Gripped this week. Aaron Pardy writes that Aiden Roberts made the first ascent of the V14 The Bee’s Knees, which Roberts called, “One of the finest boulders in the Valley.” U.K. climber Roberts says Randy Puro found the tall, steep line. For logistical reasons, Roberts couldn’t work the line on top rope, so he used ladders and the help of his friends, Katie Lamb, Keenan Takahashi, and Shawn Raboutou, who helped him work out the moves.

No stranger to hard Yosemite bouldering, last year Roberts made the second ascent of the V16 Dark Side. In 2025, he racked up the first ascents of seven lines V13 and harder, including two V15s.

Roberts posted this image on Instagram on January 5, 2026.

On Dec. 31, Outside published Rescues Were Way Up in Yosemite National Park this Year. We Dug into the Numbers by Gavin Feek. Feel reports:

Outside reached out to the National Park Service to comment on the story, and the agency provided updated metrics on rescues. As of November 12, Yosemite has conducted 235 SAR events in 2025. That’s the most since 2018.

2018: 235 SAR calls, 4,161,087 visitors

2019: 225 SAR calls, 4,586,463 visitors

2020 (*COVID): 112 SAR calls, 2,360,812 visitors

2021: 214 SAR calls, 3,343,988 visitors

2022: 196 SAR calls, 3,812,316 visitors

2023: 178 SAR calls, 4,057,237 visitors

2024: 194 SAR calls, 4,285,729 visitors

This week, YCA founder Ken Yager shared his story of climbing Horse Chute on El Cap. For the feature story, I interviewed Norm Pelak, a Merced, Calif.-based climber I often climb with. Although we’ve mainly gone cragging at spots like Sentinel Creek, Lower Yosemite Falls, Pat and Jack, and the Cookie, Norm does it all, and he loves big wall climbing. Though we’ve known each other for years and I had heard about his rescue before, it was good chatting with him to learn more about his first trad leads and his progression. Interestingly, his first trad lead was Nutcracker, where, after a quick ground rehearsal, he placed cams and built anchors under the watchful eye of his more experienced climbing partner, he set off, led the whole thing, it took all day, and he did it without incident. “I can’t believe that was my first trad… my partner was like, ‘All right, go for it,” he says. Later, while climbing a route that turned out to be the 5.12b R Duty Now For the Future (he didn’t know what it was at the time)—where he wanted to bring up his portaledge and experience El Cap a pitch off the ground—he took his first trad fall, which was on an R-rated pitch. He pulled out two pieces and decked out, requiring a helicopter rescue. Read more after Ken’s Founder’s Note.

Chris Van Leuven

Editor, YCA News Brief

SAVE THE DATES!

We’re building the first ever YOSEMITE FILM FESTIVAL & STORYTELLER SUMMIT and we want you to join us.

The first of this annual event will be:

May 21st - 24th, 2026

Campground reservations open January 15th at 7AM for this time period.

More details coming soon.

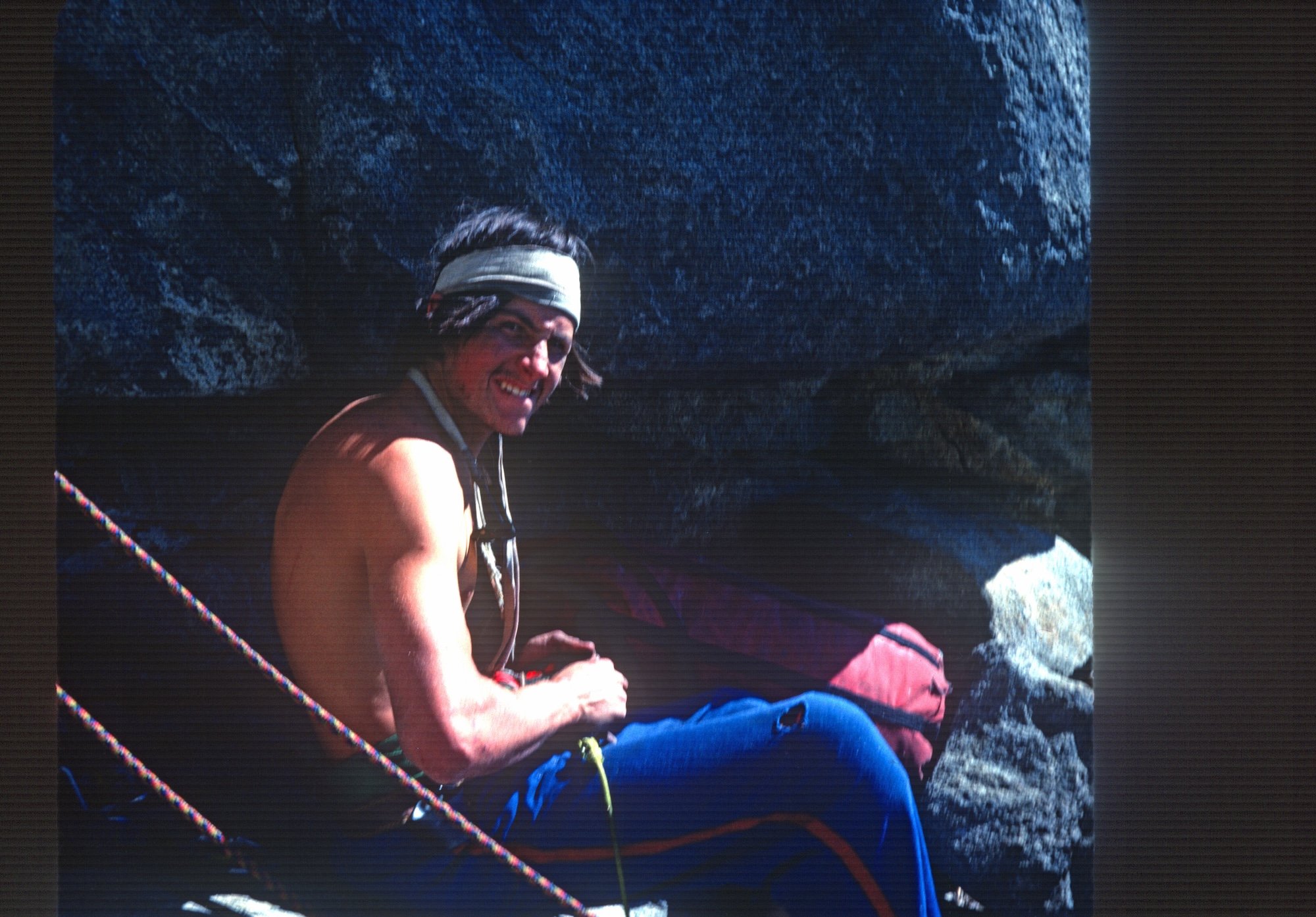

Pelak on the Dihedral Wall. Photo: Pat Curry

Building a Life Around Climbing in Yosemite: Norm Pelak

“My favorite climb is always whatever I did most recently,” says Pelak — the Merced-based hydrologist and devoted Yosemite regular.

It’s early January, and when I call Norm Pelak, it’s pouring in Mariposa, snowing in nearby Yosemite, and wet and gray where he is in Merced.

But the storms don’t seem to dampen his optimism. “I’m always surprised when I go out in December, and the weather is perfect, and you’ve got the place to yourself,” he tells me.

From his place in Merced, Pelak looks out at his newest project: a recently purchased ex-Amazon cargo van he’s turning into a climbing rig. He’s already stripped the shelving and is deep into the clean-out phase, debating whether to rent a storage unit or keep working on it out on the street.

Over the holidays, Pelak traveled to New Orleans for a conference — his professional background is in hydrology, and he works on flood-forecasting systems — before heading back to Grand Rapids, Michigan, to visit family. We have a quick chat about the flooding in Marin County, then shift to climbing, where Pelak tells me about his first climbs and his 30-foot grounder.

From the Southeast to the Gunks

Pelak first touched plastic and rock in a college climbing class at the University of Alabama. He bouldered on Southern sandstone, climbed a bit in North Carolina, and later in the Northeast, where his first multi-pitch came on one of the country’s most famous lines — High Exposure at the Trapps in the Gunks. Mountain Project calls it “flawless.”

“There wasn’t a line at the base,” he says. “My partner looked at me and said, ‘We’re doing this right now.’ I remember thinking, ‘man, this feels pretty serious.’”

Choosing Merced Because It’s Close to Yosemite

“I went to undergrad in Alabama, grad school in North Carolina and New Jersey, and moved here in 2019,” he says. He earned a PhD in Environmental Engineering from Duke University (2013–2019) and was a Visiting Scholar in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at Princeton University (2017–2019).

Pelak didn’t move west just for work. Yes, he came to Merced to do research in mountain hydrology and later to teach calculus at UC Merced, but Yosemite was part of the plan from the start. “Merced — that’s close to Yosemite,” he says. “I made life choices that would lead to more climbing.”

During the week, he trains at Alpine Climbing Adventure Fitness in Ripon with friends; on weekends, he drives to the Valley. Today, he works as a hydroclimatologist at the Hydrologic Research Center.

Nutcracker: The First Yosemite Trad Lead

For many climbers, Nutcracker (5.8, 5 pitches, ~500 feet, Manure Pile Buttress) is the traditional Yosemite baptism. For Pelak, it was his first Valley route — and his first trad lead.

“It took us like eight hours,” he says. “I didn’t fall — which I’m very happy about.” Under the watchful eye of his more experienced climbing partner, he placed cams at the base and practiced making anchors. Then he just went for it, remembering how his placements improved the higher he went, thanks to his partner’s feedback.

He laughs, remembering one key lesson: tight shoes and crack climbing don’t mix. By the end of the day, he’d learned as much about foot pain as about gear placements. Today, he climbs in comfy crack shoes in Yosemite, not down-turned gym climbing or steep-sport shoes.

“When I moved to California in 2019,” he says, “that’s when it really exploded — climbing became the thing that I do.”

The 2019 Fall That Changed Everything

That same year, he took a near-fatal climbing fall. Pelak was climbing a rarely done line just right of the Nose on El Capitan, randomly getting on the 5.12b R Duty Now For the Future, having no idea what it was, planning to fix a line, haul gear, and spend the afternoon on a portaledge — a casual wall sampler. Midway up, he fell, ripped his two top pieces (out of four), and hit the ground, taking a 30-foot fall. He broke ribs, cracked vertebrae, and hit his head hard (helmet on). Luckily, he’d chosen one of the Valley’s busiest walls: rangers were on scene fast, and he was evacuated by helicopter to a hospital in Modesto.

Looking back, he recalls his lesson there, “My enthusiasm was outpacing my increase in skill,” he says. Recovery took three months, and he was back in the gym by January and climbing in Yosemite again by February.

Big Walls, First 5.10d and a New 5.11 Goal

Since then, Pelak has become a steady presence in Yosemite — he’s up here every weekend and continues to make progress. He’s now climbed El Cap multiple times, including the Nose, Lurking Fear, Tangerine Trip, and Zodiac. His goal this year is to become more efficient in aid, move faster on the rock, and break into 5.11.

A month ago, he did his hardest trad lead, the 5.10d Catchy. “I’d fallen off the last move like three times,” — one of which was his second-ever trad fall—he says about Catchy (5.10d, Cookie Cliff). “So I decided to just go for it.”

As for climbing the grades, “I’m not super motivated by that,” he says. “It’s about who I’m climbing with and the vibe.” But he’d still like to break into 5.11 trad and has his eyes on the Salathé Wall on El Cap or something nearby.

For now, “I plan to hopefully get out to the Valley the next couple of weekends,” he says. “As long as it stays dry. There’s a whole lot there that I still haven’t done.”

Pelak and Steve Roach (RIP) about to start up the Zodiac. Photo: Random passerby

Pelak and Pat Curry after topping out on Lurking Fear, their first El Cap route (note the smoke from the 2022 Oak Fire which started while they were on the wall). Photo: Hikers on top of El Cap

Pelak on Oz in Tuolumne. Photo: Shu-Yuan Liu

Horse Chute

Founder’s Log | By Ken Yager

Mike Corbett, Chuck Goldman, and I were the first in our friend group to complete a route on El Capitan. When we got back down to the Valley floor, we felt like heroes.

It was August of 1977. We completed the Triple Direct, which was known as one of the easier routes on El Cap. I have never found any route on the Captain easy.

We ran out of water in hot weather. When we summited, we left everything on top and hiked over toward the top of Yosemite Falls looking for water. It was the second consecutive drought year, and the Falls weren’t running. I did find a couple of small pools of nearly stagnant water covered in skeeter bugs. I pushed them out of the way and drank heartily. The others were more conservative.

Within ten minutes on the trail, my stomach started cramping, and I had to sit before continuing. A doctor hiking by thought I might have appendicitis and asked if he could examine me. I said okay. He became satisfied I wasn’t going to die on the trail, and he continued down. I felt better after a bit.

By the time we reached the Valley floor, we were euphoric. We had forgotten how tired and thirsty we’d been earlier that day.

A few days later, we hiked up, retrieved our gear, and stashed a couple of gallons of water on top. We were already talking about doing another route. We were hooked.

We started studying the new green George Meyers topo guidebook to choose a climb. The guide was a ring binder so you could take the topo out and bring it with you on the climb. We were intimidated by the right side of El Cap, so we chose one called Horse Chute. We picked it because it had only one A4 pitch, and the mandatory free climbing was 5.9. It was a Charlie Porter route, and he had a reputation as a badass. We wanted to challenge ourselves and up the ante.

We carried loads up to the base and started fixing on the lower pitches of the Dihedral Wall, before the route veers out left. It was hot for September. The climbing was in left-leaning dihedrals and it was strenuous. This was before cams were available. Being right-handed, it was hard to place pitons. Cleaning them was easy. The ideal scenario would’ve been a left-handed leader and a right-handed follower.

We rested a couple of days before blasting off. Our bags were heavy and tough to haul. We were slow and spent the first night invitingly close to the ground.

Chuck led the initial pitch of Horse Chute, angling up left and over a little roof. Once he disappeared, I studied the topo. The next pitch was the A4, and I was a bit nervous. I hadn’t done one before.

Chuck suddenly yelled, “Off belay,” and the trail line was fixed. It was time for me to jumar up the rope and help Chuck with the hauling. Mike would clean the pitch after the haulbags were released.

I lowered out left until I was hanging 150 feet below Chuck and started ascending. A piece of white paper went floating by.

What was that?

Oh my God. It was the topo—the only one we had. I had left it in my lap instead of putting it away.

I started running back and forth on my jumars, trying to grab it. It kept fluttering just out of reach. It blew over to the right toward Mike, and I saw him leaning off the anchor, swinging his arms for it. It hovered above him for a while and then floated back in my direction. I resumed chasing it, to no avail. It disappeared around the corner.

I felt like an idiot and started jumaring again.

Then the topo came whipping back. I made one more missed grab and it shot up the rock. Chuck suddenly yelled down, “I got it!” We couldn’t believe it. Morale was suddenly high.

I got through the A4 section okay, and it didn’t seem too difficult. That got me psyched, so I wasn’t paying attention for the rest of the pitch. I remember throwing a sling over a knob and stepping out of my aiders onto the knob to start free climbing. The knob wasn’t very good, and a crystal was holding the sling in place.

As I stepped, the crystal popped and flew over my shoulder. I watched with horror as the sling rolled off the knob, and suddenly, I was airborne. I flew 60 feet before Chuck caught me with a hip belay. Fortunately, it was a clean fall, and I wasn’t hurt. Chuck’s hands might have hurt.

I climbed back up through the A4 section and finished the pitch without further issues.

Once the bags were hauled and all three of us were at the anchor, we looked at the next section—the mandatory free climbing, the 5.9 face pitch. I was the better free climber, and neither Chuck nor Mike liked the looks of it. They decided it was my pitch. I didn’t like the looks of it either.

I climbed up and to the right to a grainy seam that slanted left over a bulge. The crack was shallow, and all I could fit was a copperhead. Knobs and features led out left. It was tough free climbing, and it felt like forever before I reached a crack that took decent pro.

EBs were the preferred shoe at the time. They were better suited for edging than for smearing on knobs. I reached the anchor and felt so happy. We were past the crux free and aid pitches.

I looked up at the next section, and it was the wettest, slimiest pitch I had ever seen. We spent the night underneath it, dreading it.

By morning, Mike and Chuck had voted to climb straight to the 10th pitch of the Dihedral Wall and finish there instead. We could see a piton on the right, wedged in a left-facing corner of a 15-foot-tall pillar. I was disappointed, but I wasn’t eager to climb the slimy section either.

Mike headed out toward the fixed piton. When he got to the base of the pillar, he screamed, “It’s loose! Watch me!”

Mike stepped back, left to another crack, and was able to aid around the loose pillar and reach the ledge on the Dihedral.

I lowered the bags after Chuck got to Mike and started cleaning the pitch. Gravity kept forcing me over the pillar. I bumped it, and the piton began to come out. I pushed it back in with my hand and steadied the pillar. I made it past without knocking it off and sparing me—and our lead line.

My heart was beating like crazy by the time I got to the others at the anchor. I had just clipped in when we heard a metallic sound followed by a grinding sound. The piton had fallen out, and the pillar followed.

We leaned out and watched it break apart on the slab below, granite dust clouds forming at each impact.

That was close.

We spent the night on the ledge, which was nice. It was the only one for the first 2,000 feet of climbing.

The next morning, we began climbing the awkward, left-leaning corners. We weren’t moving quickly, and it was tiring. It was also covered in vegetation, and we found ourselves pushing through dry sticker bushes that looked like tumbleweeds.

Chuck and I ran out of cigarettes. Chuck rolled up some of the sticker bushes and lit one. I took a few rough hits and decided that was enough. Chuck rolled up several and seemed to enjoy them more than I did.

In the middle of day five, we ran out of food and water. We spent a thirsty evening with a full day of climbing still to go to get to the top.

The next morning, we were sluggish and dry-mouthed, but we kept climbing and reached Thanksgiving Ledge, which was huge. We walked left for several hundred feet, shuttling bags and equipment to the final part of the climb.

It was hot, and we found a cave to get out of the sun and rest. In the back of the cave, I saw two cans of sardines. I felt like I had won the lottery. We opened them and shared them. They saved us.

We got some energy back, and once the sun was setting, we started climbing for the summit. We topped out at midnight.

We looked all over for our water stash but couldn't find it in the dark. We spent another thirsty night and didn’t sleep much. As soon as it started getting light, I got up and saw the water—less than a hundred feet away—and carried it back to where we’d been sleeping.

We sat in our sleeping bags, chugging water and watching the sunrise.

Shortly after, we packed up and started walking over toward the top of Yosemite Falls and down the trail to Camp 4.

Once again, by the time we reached the Valley floor, we were euphoric. We had forgotten all about the hard work, the thirst, and the hunger, and we couldn’t wait to get back up there again on another route—maybe a slightly harder one on the overhanging right side this time.

Funny how climbing is.

PHOTO OF

THE WEEK

Nick Miranda on Super Slacker Highway, Pat and Jack Pinnacle. Photo: Chris Van Leuven

Stay up to date on the latest climbing closures in effect!

Get your permits, do your research, and hit the wall!

Visit the Yosemite Climbing Museum!

The Yosemite Climbing Museum chronicles the evolution of modern day rock climbing from 1869 to the present.

The YCA News Brief is made possible by a generous grant, provided by Sundari Krishnamurthy and her husband, Jerry Gallwas