EDITION 36 - DECEMBER 5, 2025

Your window into the stories, history, and ongoing work to preserve Yosemite’s climbing legacy.

A Note from the Editor

Climbing in Yosemite this week (Dec. 3) was marvelous. John Scott led, and I followed Homeworld at Parkline, which stayed lit by the warm sun throughout our climb. Now age 60, Scott moved smoothly and—when he needed to—boldly, even as fine dirt coated many of the edges high on the route, making the climbing slippery as the bolts grew farther apart.

Sunshine with intermittent light cloud cover is expected in Yosemite this upcoming week, with lows in the 30s and highs in the 60s.

Climbing News

Sasha DiGiulian has completed the Direct Line/Platinum Wall on El Cap. Numerous outlets have reported on her ascent. See her Instagram post below, where she wrote:

On Wednesday, November 26, I successfully free climbed PLATINUM (The Direct Line), El Cap’s longest free climb, stacked with 39 pitches of almost entirely 5.12–5.13d. I led every crux pitch.

Read the press release here and the latest feature here at Redbull.

In other El Cap free-climbing news, earlier today (on Dec. 4), Jane Jackson posted on Instagram:

I’m really proud of myself for sending the Free Rider last week. I climbed the route twice in the past month and had a blast obsessing over it with friends new and old. Flying up the wall with @ericbissell in a flowy blur of wall climbing logistical harmony was powerful, humbling, and so much fun.

Park News

A new entrance fee structure begins in Yosemite and other national parks effective Jan. 1, 2026. Here is the breakdown, (published Dec. 1):

America the Beautiful Annual Pass for Nonresidents & International Visitors will be available for $250 USD. It provides unlimited entry for one year to all U.S. National Parks, including Yosemite. The pass covers all passengers traveling in a single private vehicle and also covers up to two motorcycles.

Passholders will not be required to pay the $100 USD nonresident surcharge at the 11 designated “special parks,” which include Yosemite.

For those who do not purchase the pass, each nonresident entering Yosemite National Park (and the 10 other designated parks) will pay a $100 USD per-person entrance fee, per park.

Please note: Entrance-fee-free days do not apply to nonresidents or international visitors.

Up Next

This week, for Ken Yager’s Founder’s Note, he remembers the late Tom Frost (June 30, 1936 – Aug. 24, 2018) and his key role in the early days of the Yosemite Climbing Association. In this article in Outside, I wrote of Frost, “The Californian pioneered many of the most famous routes in Yosemite during the Valley’s Golden Age.”

Speaking of Golden Age climbers, yesterday I talked to Rich Calderwood, who assisted on the first ascents of The Nose and the East Face of Washington Column (Astroman)—though he was not on the summit team. For nearly two hours, he shared stories of his early Yosemite climbs: belaying Warren Harding on the Great Roof, eating cold soup high on El Cap, and crafting three Stovelegs used on the Nose.

See the feature on Calderwood below.

Chris Van Leuven

Editor, YCA News Brief

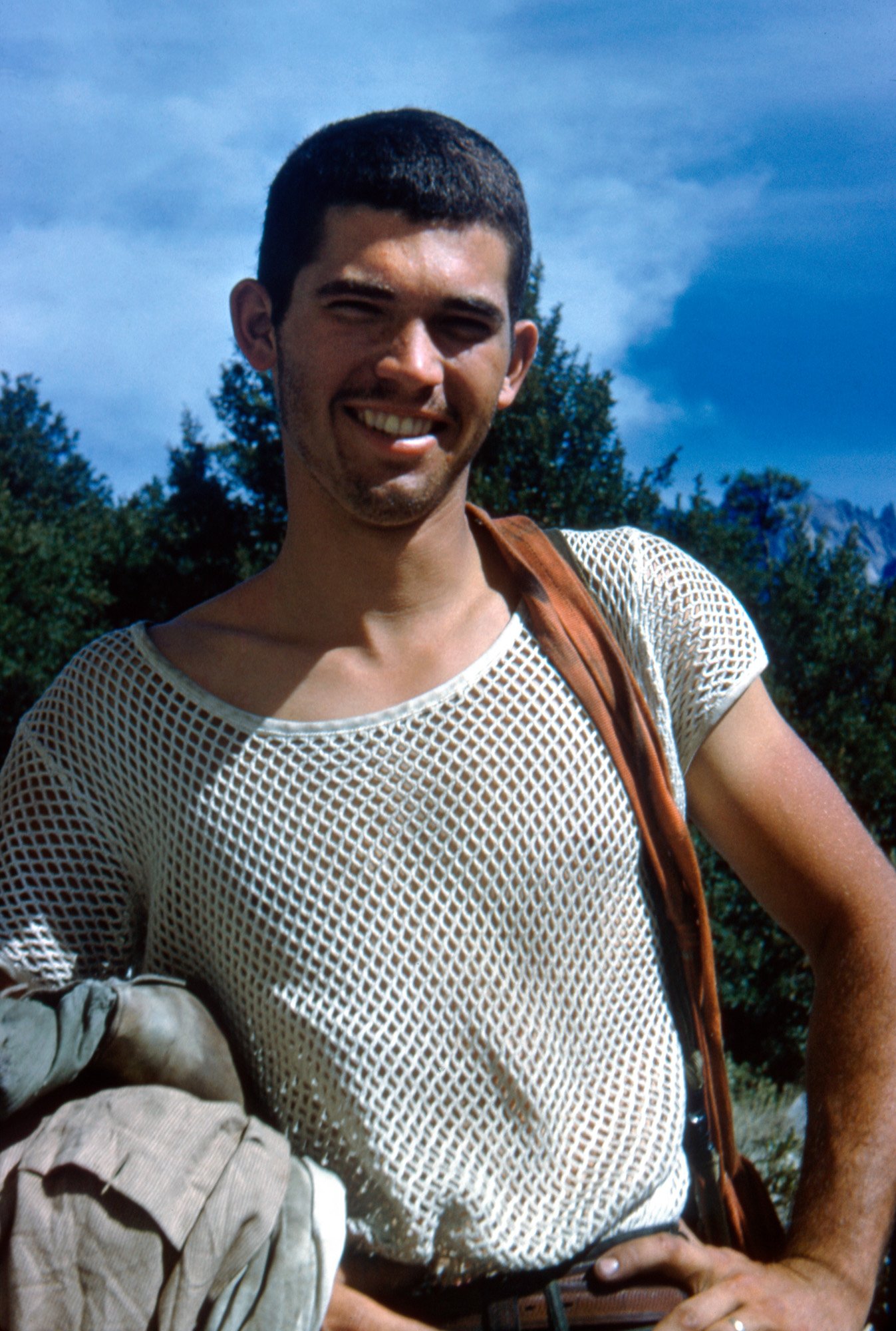

Rich Calderwood ascending fixed lines on the Nose. Photo: Courtesy Wayne Merry

Rich Calderwood: Early History of the Nose and the Stoveleg Pitons

An early contributor to Yosemite’s Golden Age, Calderwood belayed Harding on the Great Roof, assisted with the East Face of Washington Column (Astroman), and built three of the seven Stovelegs.

“I’m 88, and I started climbing when I was 15,” Rich Calderwood tells me from his home in a rural area outside Fresno (near Sanger), where he has lived since childhood. A Golden Age climber, at age 21 Calderwood spent roughly 13 days on the first ascent of the Nose—though he was not on the final push—and contributed to several early Yosemite first ascents, including Phantom Pinnacle, Left (500’, 5.9, 1957), Arches Terrace (500’, 5.8, 1958), and Coonyard Pinnacle (400’, 5.9 R, 1961).

Climbing in the 1950s: Body Belays, Bowlines on Coils, and Modified Hiking Boots

Back then, climbers didn’t use harnesses. As Calderwood remembers:

We tied the rope directly around the waist—two or three turns of rope for a little bit of cushioning—and used a bowline on a coil,” he says. And Footwear was equally primitive: Initially, I just had hiking boots. Later, I ripped the soles off my shoes, purchased Vibram soles from a shoemaker, hand-stitched and glued them on, and that became my climbing footwear.

And since mechanical ascenders didn’t exist yet, the team used prusik knots on stiff, minimally dynamic ropes. Calderwood recalls, “The nylon ropes or Goldline… there was a certain amount of stretching, but not much—not compared to the Perlon ropes, which are much safer, but they didn’t exist here yet.”

When ascending ropes, climbers clipped heavy loads to the rope around their waist and patiently, exhaustively slid one prussik up at a time. Calderwood found his own way of speeding up the brutal prussiking:

What I ended up doing, which made things much faster, was to hang from the chest loop, pull both legs up high into a deep squat, and then stand up. I could go a little better than 500 feet per hour on fixed lines. And it was strenuous — hanging from the chest loop and pulling both legs up like that put a lot of strain on the upper body.

Early Climbs

A high school friend introduced Calderwood to climbing, clarifying that he didn’t mean hiking up hills—he meant climbing vertical cliffs. Calderwood was immediately intrigued and asked to tag along next time he went out.

His first outing, with the Sierra Club, was at a cliff above Hospital Rock Campground in Sequoia National Park. On that very first day, “I found, down in amongst some leaves, a couple of steel carabiners and several pitons. It was very exciting—the first time I ever went rock climbing, and I already had some equipment.”

His first Yosemite climbing trip was a four-day tour: Overhang Bypass, a peak near Tuolumne, but he can’t recall the name, Arrowhead Pinnacle, Cathedral Peak, and Eichorn Pinnacle.

After that, he began regular visits to Yosemite that continued for years.

The East Face of Washington Column

Barely 21, Calderwood met Warren Harding through Mark Powell, who had been helping Harding on the route but was out after severely breaking his ankle on a climb, getting benighted before making it to the hospital, where he developed gangrene and spent nearly two months recovering.

Harding—already deep into attempts on the Nose—decided to test Calderwood and George Whitmore (who would later complete the Nose with him) on the East Face of Washington Column before bringing them onto the project. The two recruits spent a weekend helping Harding and team advance the route, and Harding was sufficiently impressed.

The famous route Astroman did not yet exist; this was simply the East Face in its pre-modern form. Says Mountain Project: “FA” Warren Harding, Glen Denny & Chuck Pratt, July 1959, FFA John Bachar, John Long & Ron Kauk, May 1975.”

Rich Calderwood eating canned goods on El Cap Tower. Photo: Courtesy Wayne Merry

The Nose

When Calderwood and Whitmore arrived, Harding’s team had already fixed significant amounts of rope on the Nose. Siege tactics were required: hauling, rappelling, establishing anchors, and constantly re-ascending fixed lines. Due to the massive undertaking, crowds gathered in and around El Cap meadow, backing up traffic. Recalls Calderwood:

There was a lot of pressure to do that, I guess, on Harding from the Park Service. They wanted to get this over with. You got some nasty letters — I’ve got a copy of some letter from some superintendent of the National Park Service, not just the local park, but nationwide — saying that this was a stunt and a publicity trick and it wasn’t really legitimate mountaineering.

Starting in September 1958, Calderwood spent 13 days on the wall, helping the team reach its high point. He recalls chowing on cold Campbell’s soup “just cold out of the can. Vegetables, beef or something, chicken noodle, something like that.

Though Calderwood’s preferred style of climbing was free rather than aid, he enjoyed being up on the wall; however, even back then, he saw the free-climbing potential at various sections. This included the Stovelegs.

“I thought, you know, if this was 50 feet off the ground, it wouldn’t be an aid climb. People would be doing it as a jam crack — it’s a jam crack. You don’t have to do aid on something like this. But when you’re 1,400 feet or whatever above the ground, psychologically it was a big factor.

One of his major tasks:

In addition to restocking camps, he rigged a 600-foot spool of 7/16 nylon rope down from Camp 4 in the Gray Bands to Dolt Tower, placing hauling bolts every 120 feet.

Later, using a body belay, he held the rope while Harding led the Great Roof and cleaned the pitch.

On Not Finishing the Climb

He recalls:

I was working full-time, a full-time student, and married, and I got my wife pregnant after I came down from the climb in September. So, I had a pregnant wife, a job, and school, and I really had conflicting feelings.

I knew that if I stopped and dropped out, I’d regret it. So, when I finally made the decision to go down and stay down, I left my slings and gear up on the ledge so I couldn’t go back up. I couldn’t change my mind.

It was a difficult decision. I was pretty upset about it—pretty emotional.

Ken Yager told me that Caldewood retreated from the climb when the team was only one or two days from the summit.

Stovelegs

By the time Calderwood joined the Nose team, the climb was already far above the Stoveleg cracks—but the team needed more of these unconventional pitons.

Harding wanted to know if Calderwood could make him some, so Rich visited several scrap yards. When he told the cashier his plan to cut the legs off a perfectly good stove, the clerk refused to sell him a four-legged one. Calderwood then found a three-legged stove, which the clerk considered sufficient. He picked up three porcelain-coated mild steel legs for a dollar each.

I bent the shape, did some cutting and fitting, and had my uncle do some brazing. I put a ring on it and shaped them a little differently, so they weren’t as big as the original four.

There were complaints from the team that they weren’t as big as the others, and I didn’t get all the porcelain off. When they pounded them, the porcelain tended to chip and fly off, and it was dangerous. So, I reworked them and beat on them until the porcelain was chipped off.

Knowing these unique pitons would someday have historical value, his only condition for the team was to borrow the pitons and return them at the end. The original goal was to haul the gear out, but “They said it was too much weight, and they started cutting things loose. A lot of things hung up in cracks and were lost.”

Calderwood lost one on the Folly above Camp 4, and Tom Rohrer fished it out in 1973. He later donated his final Stoveleg and several pitons to The North Face’s historical collection. “Whitmore said they were historically significant and asked if he could have one to preserve in the collection, so I gave him one. That left me with none.”

Continues Calderwood. “I’ve seen some of the Stovelegs in the museum collection, and I think at least one of them is one of the ones I made,” he says.

To see the Stovelegs, including the one found by Rohrer, visit the Yosemite Climbing Museum in Mariposa.

Portrait of Rich Caldwerwood. Photo: Wayne Merry

Alex Honnold and Tom Frost in El Cap meadow. Photo: Ken Yager

Tom Frost

Founder’s Log | By Ken Yager

I first learned about Tom Frost in 1971, the year the shift to Clean Climbing truly began. Several companies started making their own versions of hand-placed protection, but the best by far was made by Chouinard Equipment. They produced Hexes and Stoppers in different sizes, which worked perfectly in California granite. Chouinard Equipment was a partnership between Yvon Chouinard and Tom Frost.

I had just started climbing and spent much of my free time after school at Alpine Products, our local outdoor shop. I’d go there to read climbing magazines and catalogs. That’s where I picked up my first Chouinard Equipment catalog. The catalogs were beautifully designed, featuring essays, photos, and of course, the gear and pricing. I absorbed every word, reading my first two catalogs over and over.

In 1997, Tom Frost sued the National Park Service to protect Camp 4, which was slated for hotel development. He contributed roughly a quarter-million dollars of his own money to fund the effort. Attorney Dick Duane represented the plaintiffs, and several others added their names to the lawsuit. Against all odds, they won.

In 1999, the victory was celebrated at the Lower River Amphitheater, generously hosted by the American Alpine Club. Climbers came out of the woodwork, and attendance was huge. Law Enforcement was nervous and stationed Horse Patrol around the perimeter, but it turned out to be a joyful reunion. Many climbers spoke on stage. A man with white hair walked onstage, and someone introduced him as Tom Frost. Even though I knew who he was, I had never seen him in person. I didn’t get to meet him that night—he was surrounded by people offering congratulations.

About a year later, I saw a Porsche pull into the Camp 4 parking lot. Tom stepped out with his climbing shoes and headed toward Swan Slab. I remember being impressed. I was guiding for YMS at the time and spent many hours at Swan Slab teaching classes. Tom showed up regularly, and we began talking and eventually introduced ourselves.

He always wore white clothes, and with his white hair, he was easy to spot from a distance. He had a cheerful presence, a snaggletooth grin, and a twinkle in his eye. He often looked like he was up to mischief.

He was climbing El Cap routes with his son during that period and would train by bouldering around Camp 4. We spoke frequently. I told him about the historical artifacts I had been collecting and that I was working on the paperwork to form a non-profit. He was so encouraging that I asked him to join the board. He agreed. I couldn’t believe it.

In 2003, I founded the Yosemite Climbing Association as a 501(c)(3). Tom and I grew close; he often drove to the park to support me in meetings with NPS officials. I called him regularly to share ideas. He was always supportive and gave thoughtful advice, usually with his distinctive chuckle. Our main goal was to secure a permanent climbing display in the park—a seemingly impossible task. I called him so often I memorized his number, and I still remember it today.

Tom was into sailing and bike racing. He even designed a steel racing bike frame. He was a co-founder of Chimera Lighting. He didn’t talk much about his accomplishments; he preferred helping others realize theirs. He nearly reached the summit of Annapurna but began to feel the effects of altitude. On his way back down, he collected several rocks and brought them home. He displayed them at his house in Oakdale.

Tom served on the YCA board for 15 years, until his passing in 2018. Two hours after I heard the news, I received a call from Park Superintendent Mike Reynolds. He had just signed off on a permanent climbing display in the Visitor Center. Emotionally, it was too much, and I broke down crying.

How I wish I could have called Tom and shared the news with him.

PHOTO OF

THE WEEK

John Scott midway up Homeworld, Parkline Slab. Photo: Chris Van Leuven

Stay up to date on the latest climbing closures in effect!

Get your permits, do your research, and hit the wall!

Visit the Yosemite Climbing Museum!

The Yosemite Climbing Museum chronicles the evolution of modern day rock climbing from 1869 to the present.

The YCA News Brief is made possible by a generous grant, provided by Sundari Krishnamurthy and her husband, Jerry Gallwas