EDITION 33 - NOVEMBER 11, 2025

Your window into the stories, history, and ongoing work to preserve Yosemite’s climbing legacy.

A Note from the Editor

I revisited Yosemite over the weekend and saw that many of the fall leaves from the week before had already dropped. While some trees still displayed color, many now stood bare. It’s still stunning — bursts of red and gold still brighten the valley, just fewer of them now.

That day, Pat and I had planned to get on the 2023 James Gustafson route, 36 Chambers, on Chapel Wall — the only climb that I know of that tops out the formation. But I wasn’t particularly inspired by the loose-looking pitches in the topo, so instead we went with our old standby: the four-pitch Great Escape, while another team did the neighboring Killa Beez.

Climbers on Killa Beez, Chapel Wall. Photo: Chris Van Leuven

On the way out that afternoon, I looked up at El Cap and saw pink alpenglow illuminating the face near Horsetail Fall — the same location that becomes the famous “Firefall.”

It’s only a few months until Firefall season. As Yosemite.com writes, “During mid to late February, the waterfall begins to light up five to fifteen minutes before sunset,” when conditions align just right.

Weather is headed to California this week. As Greg Porter at the San Francisco Chronicle reported:

A much stronger, wetter storm will hit California this week. Here’s a timeline

Estimates from the National Weather Service show the heaviest rain will fall from 10 p.m. Wednesday though 10 a.m. Thursday.

In the Sierra, the storm arrives with a surge of warm air, so snow levels will start above 8,500 feet. But much colder air will quickly move in, and snow levels will drop rapidly by Thursday evening.

By Friday evening, more than a foot of snow is likely to have fallen at higher elevations in the Sierra. A few inches of snow is likely at lake level in Tahoe, with the area mountains generally in line to receive 5 to 10 inches.

Tioga Road (Hwy 120 through the park) and Glacier Point Road to close

Date Posted: 11/10/2025Alert 1, Severity closure, Tioga Road (Hwy 120 through the park) and Glacier Point Road to close

Tioga Road (continuation of Highway 120 through the park) and Glacier Point Road will temporarily close on Wednesday, November 12, at 6 pm due to a forecast of snow. Snow is possible on other roads; be prepared for tire chain requirements and other road closures.

Climbing News

Just this morning (Nov. 11), I saw on Instagram that Pietro Vidi sent Meltdown at Upper Cascade Falls (60 feet, 5.14c PG-13), writing:

“Meltdown”

Legendary route, crazy vision from @bethrodden back in 2008, this thing was definitely ahead of its time!

Classic Yosemite “power tech” style, where the holds are actually decent, but the feet are really bad, the body positions complicated and moves feel very insecure.

Stoked to add my name to the list of people who have climbed it!

As for this season’s speed ascents, RockClimbingYosemite.com reported:

Lurking Fear, El Capitan — 7:19 (Oct 28, 2025) — Taylor Martin (Solo)

Squeeze Play, El Capitan — 10:07 (Oct 25, 2025) — Brant Hysell, Dan Gosselin

Tangerine Trip, El Capitan — 7:57 (Oct 19, 2025) — Brant Hysell, Dan Gosselin

Taylor Martin wrote about her Lurking Fear solo on Instagram.

Brant Hysell posted on Instagram about Squeeze Play:

Squeeze Play – A3, 20 pitches, and another El Cap speed record at 10 hours, 7 minutes. After Tangerine Trip last week, we wanted a new El Cap wall to push in a day — some fresh terrain. We’d heard Squeeze Play was a small step up from Lurking Fear. That was wrong.

It’s a significant step up — multiple pitches of beaks, a 150-foot traversing roof with upward-driven knifeblades, exciting cam hooks, and horizontal beaks. I’d call it a half-step down from Zodiac and a full step up from LF.

On Tangerine Trip, Hysell posted on Instagram:

Tangerine Trip — 7 hours 57 minutes, 17 pitches (5.7 A3). Always chase your heroes. Last week we climbed fast but missed the record by 65 seconds — the 9:28 held by @alexhonnold and @daveallfrey.

This time, with new tactics and a lot of psyche, we shaved off 90 minutes — bringing the record under eight hours at 7:57!

Also in climbing news, on Instagram, James Gustafson posted about his new route:

Bridezilla (Wedding Industrial Complex):

5.12b? | 13 pitches | ~1,500 feet

Gustafson writes:

Last May, I walked the Taft Point Trail with a handful of old ropes and rappelled down looking for a line. I knew there was a sport crag and an old Galen Rowell aid route nearby, but suspected the wall held untapped potential — and that was confirmed.

What I didn’t anticipate was the scale. Over the past year and a half, I’ve spent a lot of time swinging around, working out a free route up the face.

About a week ago, I finally felt ready and asked @mtaylor.gram [Mark Taylor?; link doesn’t work] to support me on a lead burn. It took longer than I expected; I forgot food, ran out of water, and somehow still managed to send.

The route still needs better bolting, more rappel anchors for a single-rope descent, and some alternate variations that look great. The name comes from all the wedding photo shoots I saw at Taft Point while hiking out — quite a contrast from topping out over the rim after a day on the wall.

Community Spotlight: Linda Jarit

Two weeks ago, while cragging at Sentinel Creek, I ran into Linda Jarit just after she’d climbed the first two pitches of Mental Block. She looked familiar. When she said her first name, I replied, “Jarit?” — and she smiled and nodded.

I recognized Linda from when I helped put together the YCA Facelift Zine a few years ago. For many years, she’s volunteered as an event coordinator for Yosemite Facelift, and her photo appeared in the zine, which is how I remembered her.

For the zine, when I asked what keeps her coming back to volunteer year after year, she said:

The gathering of the community and knowing that our work has made a positive impact on a place I love. Seeing the joy and excitement when folks return with their trash, eager to share about their day, and watching them take ownership of their environment.

I asked to feature her in this newsletter. See her story below.

Chris Van Leuven

Editor, Yosemite Climbing Association News Brief

YosemiteClimbing.org

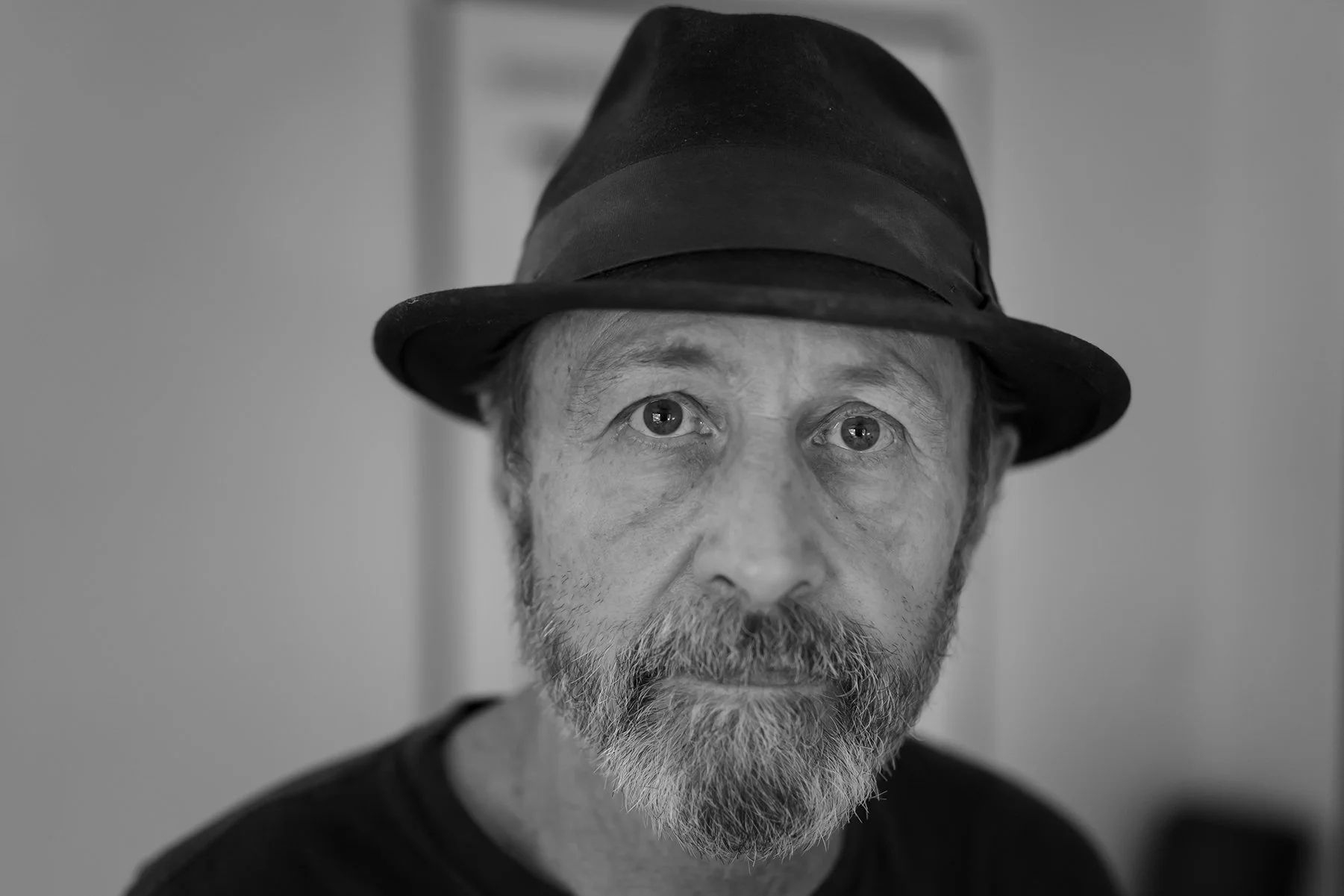

Linda somewhere in Yosemite. Photo: Eric Gable

Yosemite Facelift Event Coordinator Linda Jarit

Jarit is a first ascensionist and YCA volunteer who has climbed in the Park for three decades

As noted on the Yosemite Climbing Association (YCA) website and Facebook page:

Linda has been climbing in Yosemite since the 1990s and participating in Yosemite Facelift since the beginning. She has multiple first ascents in Yosemite and is a great mentor for newer climbers. She took a more active role in 2017, helping organize sponsors and coordinate volunteers requesting camping. Linda brings her open and friendly demeanor to the Yosemite Climbing Association. We love you, Linda!

Curious about her first ascents, I looked up her name on Mountain Project.

Among her contributions:

Beyond Lunacy (5.11c, 7 pitches, 2008) Eric Gabel, Linda Jarit, Kevin Willoh, FFA 2009 Chad Suchoski, Mike Cane, Reed’s Pinnacle.

A fun adventure to the top of Reed’s. Good climb to do during Fall and Winter months. (Linda’s favorite).

Adventures With Linda (5.11b, 6 pitches, 2004) — established with Eric Gabel at Wildcat Falls. The route description calls it a chill, interesting, dirty day out with a mindset for keeping it real.

Edge of Absurdity (5.9 PG-13, 7 pitches / ~1,000 ft, 2005) — also near Wildcat Falls, with Eric Gabel, Chad Noble, and Brent Botta. The description reads:

The climbing and rock are good in a few spots (and dirty in many others), but what really makes it worthwhile is the position. It follows the lip of a very steep wall, and combined with the slab of the Cookie Sheet below, it’s an exposed and adventurous endeavor with some runouts and route-finding challenges. The descent is unique in all the Valley. Altogether, a great adventure.

She has various other routes scattered around Yosemite Valley and Tuolumne Meadows.

Talking With Linda

As we chatted that day at Sentinel Creek, I texted her a few questions about her long involvement with Facelift and climbing in Yosemite.

How long have you been an event coordinator for Facelift, and what keeps you coming back?

I believe I became the event coordinator for Yosemite Facelift in 2017.

What brings me back is the chance to give back to the park. I’ve spent so much time here that it feels right to help keep it clean and beautiful. I also love the sense of community and how we all gather together each year.

How did you first get involved?

I think I just heard about it and showed up to volunteer. Over time, I got more and more involved, and the coordinator role kind of evolved around me.

These days I primarily help coordinate our core volunteers — the folks who run the event — and manage much of the camping logistics.

What do you love about Yosemite?

Wow, that’s a big question. Of course, I love the beauty and splendor, but there’s also a sense of peace, serenity, and re-grounding I get here. It’s easy to find quiet and solitude — you just have to get off the ground a little.

I’ve been coming here for more than 30 years, and every time I drive into the park I’m still awestruck. I’m amazed that I can keep discovering new places I’ve never been.

Oh yeah — and the climbing! Yosemite is a gathering place for so many of my friends and community; it feels like coming home.

I also love being here through the seasons, watching the colors and light change, and how the Valley grows quiet in fall and winter.

What climbs have you done lately?

This past weekend, as you know, I was at Sentinel Creek cragging. We got on Hari Kari, Yin Yang, and Mantra. My friend Julian rope-gunned. It was an awesome weekend — great to run into good friends and enjoy perfect weather!

Photo: Ed Hartouni

Linda Jarit at Spearfish Canyon, South Dakota. Photo: Jay Anderson

Jarit in front of Ken Yager’s truck during a Facelift event. Photo: Yosemite Climbing Association collection

Photo: Ken Yager collection

Moving to Yosemite

How an 18-year-old found home among the dirtbags, dreamers, and climbers of Camp 4 | By Ken Yager

On December 6, 1976, my father drove me up to Yosemite and dropped me off in Camp 4 with all of my belongings. It was a warm, clear day, and I was just a couple of months shy of turning eighteen. The campground had been officially renamed Sunnyside Campground, but everyone still called it Camp 4.

Once my stuff was unloaded into the parking lot, my father turned his car around and began the four-hour drive home to Davis, where he worked as a physics professor.

As his car disappeared down Northside Drive, I gathered my things and wandered into the quiet campground, filled with excitement. The place felt almost abandoned. There was no kiosk ranger, and camping was free in the winter. Other than a few tents at the far end belonging to Yosemite Search and Rescue (YOSAR), there was a small cluster of five or six tents in the center.

I decided to set up near the beginning of camp to give everyone space. I pitched a large Coleman tent I’d borrowed from my aunt and uncle — roomy enough even after I’d moved all my climbing gear and clothes inside. I hung my food in a tree, then walked over to Yosemite Lodge to check things out.

The Lodge had a public lounge centered around a giant fireplace with a conical metal hood. It became the evening hangout. People read books, played board games, and warmed themselves by the fire while slide shows or park presentations played. That old lounge would later become part of the Mountain Room Bar and half of the Cliff Room.

I didn’t know a soul.

At a vending machine, I bought a pack of cigarettes — Camel straights — not realizing I’d just purchased everyone’s favorite brand. As soon as I cracked open the pack, two or three people appeared from the shadows asking for a smoke. I handed some out and slowly began meeting a few of my neighbors.

It took about three or four days before the folks in the center of camp trusted me enough to invite me over. About eight people were living together in five or six tents, most of them with vehicles they used for storage or as living spaces. They called their camp Skull Camp — and to prove the name’s authenticity, a deer skull hung from a tree with a stick jammed in its mouth.

Two couples and three single guys stayed there full-time, with visitors joining on weekends. Over time, I got to know this tight-knit group. They were generous and loyal — and I’m still close to many of them nearly fifty years later.

There was Errett Allen, long-haired and long-bearded, and his girlfriend, Laura, both kind and welcoming. They lived in a Volkswagen van and often shared home-cooked meals. Errett and I would go on to climb together extensively on the east side of the Sierra.

The other couple was Billy “Blitzo” Serniuk and his wife, Charlene, a tall, freckled redhead with a quick smile. Blitzo was a total Frank Zappa freak — he owned every album, knew every lyric, and sang along constantly. Their van was the camp’s de facto hub for music and parties.

Then there was Gary “Crazy Eddy” Edmundson, who lived in a big white truck with a camper shell. Rick Cashner was another — the strongest free climber of the bunch — and we climbed together often in the years to come. Mike Corbett was there too, more drawn to aid climbing and big walls. We soon teamed up and climbed seven walls that year, including four routes on El Capitan.

The last regular was Chuck Goldman — a tall, charismatic cowboy type with long blond hair. Chuck was loud, charming, and always surrounded by stories (and women). It sometimes seemed like he took up climbing just to meet the Curry Company employees.

Finding My People

On my first day bouldering behind camp, I met Werner Braun, who was living in the SAR camp. We kept running into each other at the same boulders, so we teamed up. Werner showed me the classic Camp 4 problems, and we quickly became friends.

The days were mild but the nights freezing — it was the second year of a two-year drought. One afternoon, Werner led me to Yosemite Creek, which was frozen solid. Inside the ice, twenty or so large trout were frozen mid-swim. I’d never seen anything like it — and haven’t since.

Through Werner, I met Jack Dorn, another SAR regular. Jack was loud, funny, and well-liked by everyone. Tragically, he died later that spring during a rescue after stepping off the Yosemite Falls Trail in the dark.

These ten people — the Skull Camp crew and SAR friends — became my family that winter.

They taught me how to live in Yosemite and stay out of trouble. Climbers weren’t well-liked by the National Park Service or Curry Company management. Curry had its own security force armed with batons, handcuffs, and radios. Their job seemed to be keeping climbers from sneaking showers or hanging out with employees in the dorms.

Living Dirtbag-Style

From my friends, I learned about canning — collecting bottles and cans for recycling. Yosemite was one of the few places in California that paid five cents per can, so if you were willing to dig through trash cans and dumpsters, you could make up to $80 a day — a small fortune back then.

It was technically illegal, but that didn’t stop us.

I got very little sleep those first few nights because of bears going after my food. I’d chase them off, but they kept coming back, all night long. On the third night they finally got it, dragging everything off into the woods. From then on, I didn’t store food at camp. I resorted to finding food day by day, much to the amusement of Skull Camp and the rescue team.

My friends also taught me which rangers to avoid, which security guards were cool, and which employees didn’t mind climbers hanging around. I learned where to sit in a dark corner of the bar, near a small opening to the restaurant, where baskets of cheese bread would “magically” appear on the table.

We climbed together constantly, mostly south-facing routes that warmed in the sun. The Valley was empty except for us and the “weekend warriors” who came up from the Bay. The NPS and Curry employees called us C4Bs — Camp 4 Bums. We wore it like a badge of honor.

Our daily climbing made us strong quickly, and soon we were tackling harder routes. Later that year, some of us hiked to the plane crash at Lower Merced Pass Lake, returning with packs of wet marijuana, which ended up funding our climbing for much of the next year.

It was a carefree, golden time. We’d climb all day, listen to Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, Cream, and of course, Frank Zappa. At night, we rode on top of the old double-decker buses, drinking beer and smoking joints. If you sat in front of the driver’s periscope, he’d stop the bus and kick you off, so you learned to stay low.

The End of the Beginning

Like all good things, it eventually came to an end. As summer arrived, we were told we’d overstayed the time limit and were kicked out of camp. We packed our tents and gear. Some people left, but most of us stayed — each finding a cave to live in.

We still climbed together every day and hung out every night. We just had to keep a low profile to avoid getting caught by law enforcement. Despite the constant need to hide, I was happier than I’d ever been.

That first year changed my life. I knew I’d found my home.

PHOTO OF

THE WEEK

An unknown climber on the last pitch of Royal Arches. Photo: Chris Van Leuven

Stay up to date on the latest climbing closures in effect!

Get your permits, do your research, and hit the wall!

Visit the Yosemite Climbing Museum!

The Yosemite Climbing Museum chronicles the evolution of modern day rock climbing from 1869 to the present.

The YCA News Brief is made possible by a generous grant, provided by Sundari Krishnamurthy and her husband, Jerry Gallwas